The wizard mentor. Whether labeled a mystic, a wise one, a shaman, or any of a hundred other names, this archetype has appeared in stories from nearly every culture and period, and is a particular favorite of modern fantasy.

Whether it’s Gandalf…

Dumbledore…

…or Obi-Wan…

…they’re all cut from the same cloth (and obviously subscribe to the same fashion magazines). While a cynical person might call them unimaginative copies of one another — barely altered versions of Merlin — I would argue that’s beside the point.

Because these characters aren’t supposed to be reinvented from the ground up. That’s not their function in story or myth. Rather than an opportunity to conceive of something new, they’re one of the constant, familiar elements that allow us to accept all the fantastical aspects of a story that are innovative.

Whether it’s epic battles between forces of good and evil…

…schools of magic hidden in distant mountains…

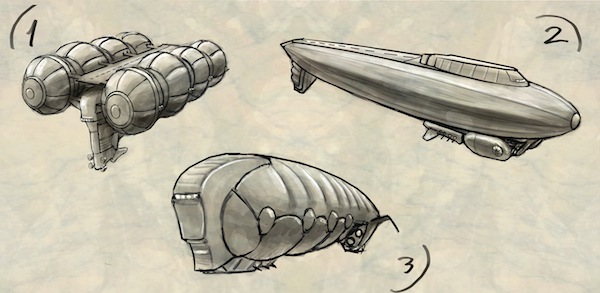

…or spaceships you really, really, really wanted to fly in as a kid (okay, even more so now)…

…the setting, the plot, the rules of the world… even the hero of the story may change dramatically, but the wizard mentor remains steadfast.

So, beyond the stable ground they provide a story, what is the function of a wizard mentor?

One classic role they fulfill is as father figure to an (often orphaned) hero. But their main goal is to steer, nudge, bribe, inspire, trick, convince, shame… basically do anything they must to guide the hero into taking the path that is their destiny, and ultimately, face the evil they will inevitably have to confront in the end.

Another aspect that I’ve always found fascinating about these characters — and one that seems nearly universal as well — is that the wizard mentor keeps secrets from the hero. Not that they don’t like and trust (or even love) their young champions, but wizards do what they must for the big picture, for the greater good. They endure the guilt for the peril they puts their apprentices in, and keep their secrets out of a desire to shelter their hero from the burden of the dark truth about their plight… their destiny… and often their slim (or nonexistent) chances for survival.

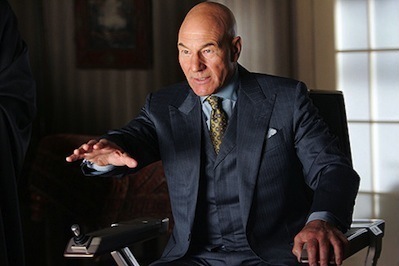

How about a few more wizard mentors you might be familiar that show they don’t always have to have long gray beards (couldn’t hurt though). Let’ see, how about the bald one from X-Men…

…or that geeky guy from Buffy…

…and how about a woman (no small task to find one, let me tell you)…

Slap a beard on her, and you’ve got Gandalf again! And if you know who she is, you’ve watched entirely too many badly written 1980’s fantasy films staring Val Kilmer. (There could be an entire discussion on the lack of women wizard mentors, but that’s fodder for a future post)

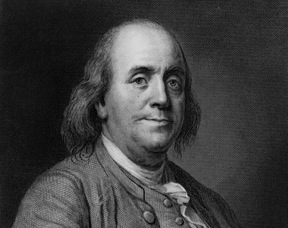

And how about one from History. I would argue that this guy fits the bill pretty closely…

Franklin fits the archetype of a wizard mentor in his relations to many of America’s founding fathers.

Ok, that was fun… but let’s get to grandaddy of them all…

Merlin…

The stock wizard mentor, recast a hundred (if not a thousand) times in countless versions of the Arthurian Legends over the last millennium, retains these core elements.

But in modern versions, he’s sometimes more of a bumbling professorial, rated-G, white magic type…

…while in others, he operates in a moral grayish area…

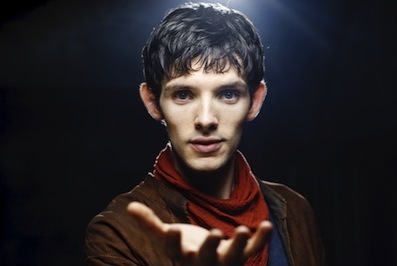

…and still other times, he’s just a teenager, learning the ropes, worried about pimples and girls (or maybe boys, unclear)…

…whoa… wait a second. If you’re familiar with the show, I know what you’re thinking. This Merlin doesn’t fit the bill! Well, although I could argue that this Merlin is still a mentor to Arthur, and is indeed keeping secrets about Arthur’s destiny from him… I’d have to agree. In my opinion, in the BBC Merlin TV Series, Merlin is not the wizard mentor…

He’s the hero.

And the man training him — Gaius — is the wizard mentor…

That looks better, no?